Oklahoma Teacher Activism in the mid 1960s

When leaders fail, communities rise: The OEA’s fight for Oklahoma’s Future

By Scout Anvar

In 1962, Oklahomans elected their first Republican Governor, Henry Bellmon, under his “Giant Stride,” no new taxes platform. The OEA Fund for Children and Public Education (FCPE) had endorsed his opponent, Bill Atkinson, but remained optimistic that Bellmon would work with teachers and properly fund schools. Two legislative sessions into his term, he had not lived up to that expectation. After reaching his desk, Bellmon vetoed Senate Bill 146, a wildly popular and bipartisan bill that would have increased teacher pay and education funding across the board. This bill had passed by an overwhelming majority vote in both chambers of the legislature, yet neither the House nor the Senate wanted to rock the boat by overriding the governor’s veto. Their inaction and desire to stay on Bellmon’s good side caused great strife for Oklahomans over the next year.

In response, the OEA Board of Directors proposed four initiative petitions that made it onto the ballot, but they all failed after a “NO” campaign ran by Bellmon and his supporters. Over 300,000 Oklahoma voters failed to vote on any of the initiative petitions. The OEA board then urged the governor to call a special session to address education shortfalls to prevent schools from falling behind any further. Citing the cost, Bellmon refused and proceeded to call a special session for oil and gas issues instead. The OEA and its members felt robbed — this was a huge punch to the gut.

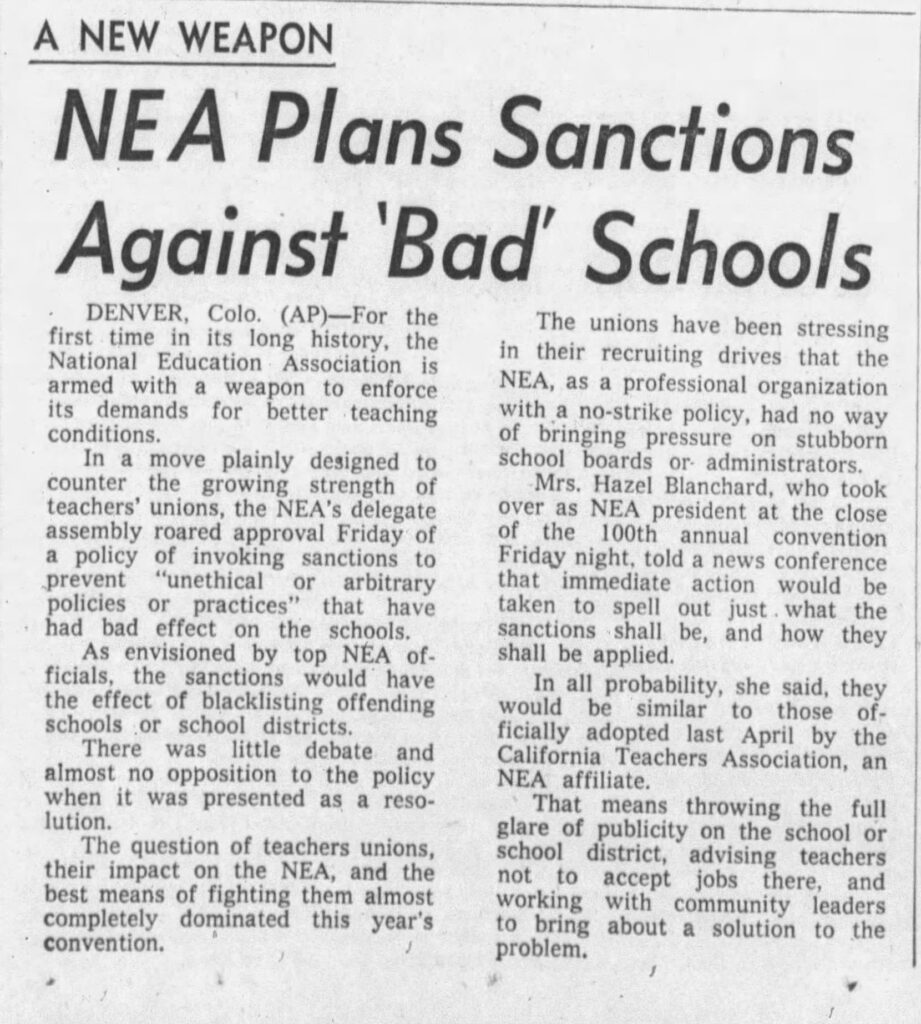

So, the OEA called for NEA backup. NEA members had introduced what they call “sanctions” in 1962 during their Representative Assembly as a proactive measure to ensure accountability from education leaders when school conditions became “subminimal” or required immediate improvement. Sanctions were used successfully in Utah a year prior to Oklahoma, so the NEA was hopeful that they could help move the needle in the Sooner State too. The NEA then launched a full investigation into Oklahoma education conditions and published a scathing report on their findings. The report contained guidance not only for the OEA, but for local business leaders, legislators, state and local school boards, religious leaders, media outlets, and all citizens. On page 40 of the NEA report, they state, “…if in truth education is too important to be left to the educators, then industrial, civil, religious, political, and news media leaders should make improved education their business and take responsibility for informing the public.” The report made its way to national media channels. This put a lot of pressure on Oklahoma leaders who, rightly, began to feel embarrassed at how poor school conditions had become. The nation was watching, and it wasn’t a pretty sight.

Once the NEA report trickled down to the general public, more and more citizens became concerned that Oklahoma was failing their children. The OEA knew how to capitalize on this momentum and with NEA’s help, began helping teachers find work in different states and discouraged big businesses from expanding in Oklahoma. These tactics took the place of a strike due to the illegality of a true strike and were arguably more effective in initiating change.

Once Oklahomans were thoroughly fired up, the association proposed a single constitutional amendment that bypassed the governor, this time with thorough and accurate media coverage. The act increased school funding by $27 million and included a 10% teacher pay raise. Voters passed it with flying colors. The NEA sanctions were finally lifted in 1965, but the real work had just begun.

While there are numerous lessons to glean from this piece of Oklahoma history, it’s most important for OEA members to remember what successes are in reach through teamwork and community organizing. During this struggle, educators in Oklahoma and across the nation came together with the general public to hold state leaders responsible for their actions — or rather their inaction. Education had, for the first time in Oklahoma, become everyone’s business. With this history in mind, we must never forget to draw on our biggest asset as professionals: our collective power.